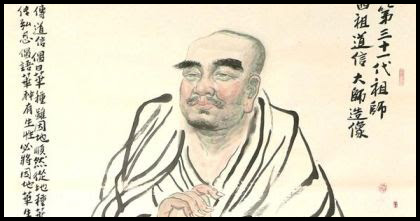

DAYI DAOXIN (580-651) 4th Chan/Zen Patriarch – also known as Tao-hsin

Daoxin was born in 580 CE and is associated with the East Mountain temple on Shuangfeng (‘Twin Peaks’) in Hunan province of central China – where he taught for 30 years. When he died in 651 CE, Daoxin was honoured by the Chinese Emperor, Dai Zong, with the title, ‘Dayi,’ which means ‘great healer.’

Red Pine, the American scholar and translator of Chinese poetry, in a very interesting YouTube interview, points out that Bodhidharma and his successor, Huike, had only a few students, while the third Zen patriarch, Sengcan, had only one known disciple. But that disciple, Daoxin, had around 500 students. So, Red Pine asks, what happened? What was Daoxin doing that attracted so many students? Pine argues that we need to keep in mind that the first three Zen patriarchs were travelling teachers. They didn’t have their own monasteries – no settled places of teaching and learning – though Sengcan did teach in a monastery of a different sect. So, one major innovation of Daoxin, the fourth patriarch, was to establish a centre for his own teaching and that centre was, according, to Pine, an ‘agricultural commune.’ Daoxin got some land in the mountains, not on a slope or mountaintop, but on a mountain basin – an area of flattish land in the mountains that could be cultivated. (Pine 2024)

The reason this is important is that prior to Daoxin’s time early Chan Buddhists continued the Indian tradition of begging and moving from place to place – dependent on the generosity of villagers, farmers and occasionally on wealthy landowners. This approach didn’t sit easy with Chinese culture, which had a strong tradition of work and practicality. Daoxin came along and said, ‘we are going to work for a living. We aren’t going to beg, we are going to grow our own food. And although we might kill some creatures in the soil as we dig and sow, we will only eat plants that we grow.’ Red Pine considers this to be the beginning of vegetarianism in Chinese Zen – pointing out that previously there was no rule against eating meat – indeed there is a legend that Gotama Buddha died due to the effects of eating rotten meat giving to him in his begging bowl. Travelling monks had to eat whatever they were given – including meat. By the time of Huineng, the sixth patriarch, there were 6,000 students in his monastic settlement – all working in a relatively self-sufficient community. (ibid) The settled teacher could gather together many students, and they could all work to provide food, accommodation and a meditation hall for themselves

This bringing together of Chan or Zen, meaning ‘meditation,’ with physical work and the cultivation of crops, means that daily life, in all its forms, becomes one’s Zen practice. Red Pine bases his observations on his experience of visiting most, if not all, of the Chan monasteries that were active in the Tang dynasty, when there was a great flowering of Chan in China, and all of these monasteries were located in high mountain basins – places where land could be cultivated, crops could be grown for food, and work could become a legitimate and crucial aspect of meditation practice. For a Chan student, surrounded by a large community of other students, ‘everything I am doing is my Zen practice.’ (ibid)

This was a major change in the development of Chinese Chan and Japanese Zen. No longer was the learning community, the monastery, dependent on others through begging, it now became a thriving community of workers who grew their own food, made pottery, designed and maintained gardens, built temples and homes for themselves and turned their daily lives into ways of being mindful, ways of practicing Zen. Instead of just zazen, ‘sitting meditation,’ students practised ‘washing dishes zen,’ ‘digging the garden zen,’ ‘sweeping the yard zen,’ ‘cooking a meal zen,’ and so on. This also opened the way for anyone to practice Zen, not just full-time monks or nuns – but anyone who wants to consider their daily life as meditation, mindful, practice. This was transformative both in the development of Zen practice and in the growth of Chan and Zen within China and Japan.

It may be useful to note that the Japanese Rinzai Zen teacher, Shinzan Miyamae, uses the term ‘do-zen’ meaning ‘meditation in activity’ – (what I think of as ‘doing-zen’) – as a complement to ‘zazen which is ‘practice in stillness.’ (Skinner 2017: 131) Though the term, ‘do-zen,’ isn’t often mentioned in Zen teachings, it seems to me that it is a very useful reminder that the way of Zen is to be mindful in whatever we are doing.

Red Pine mentions that Daoxin’s ‘daily life zen’ was the factor that attracted Pine himself to Chan or Zen Buddhism when he lived in Taiwan, rather than to another Buddhist tradition, known as ‘Pure Land’ or ‘Shin’ Buddhism. For him, Pure Land Buddhism required a belief in a state or place beyond this life, ‘a paradise that you might be reborn in.’ (ibid) He says that Pure Land Buddhism, like Christianity, is based on ‘a belief in something you cannot see’ (ibid), whereas Zen requires no such belief, it only requires one’s own energy and experience to be mindful and ‘awake’ as one goes about daily life.

Everything we do is a gateway to awakening. In this way ordinary, mundane life becomes sacred and wonderful. And this realisation, though grounded in Gotama Buddha’s teachings, we owe to Daoxin – insofar as he made it the centre of his working Zen practice.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pine Red. 2024. Red Pine – Zen Buddhism. Online at: https://youtu.be/4Xv6Jf_jDjA?si=GuLeHcomWyqVr8UP – accessed 27th April 2025.

Skinner, Julian Daizan. 2017. Practical Zen: Meditation and Beyond. London: Singing Dragon.