A brief story: the person we now know as Gotama Buddha is said to have held up a flower to his students who were gathered around him. He stands holding the flower for quite a while but says nothing. There is just silence – a man holding a flower and students waiting for him to say something – to teach them some aspect of his great wisdom. But as time passes, he says nothing. The students are puzzled and become more and more uncomfortable. What is he doing? What is going on? Why doesn’t he teach us, they think? But then one student, his name was Mahakasyapa, looks at the buddha and smiles. The buddha smiles in return. He can see that Mahakasyapa is awake and is seeing the flower for what it is – a beautiful mysterious presence that cannot be defined or described in words. The flower is just what it is – an indescribable array of colours and tones, held in a form we call a hand. Zen Buddhism traces its origins to this wordless smile-to-smile encounter between two people.

The word ‘Zen’ is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of a Chinese word, ‘chan’, which is a shortened form of ‘channa’, which, in turn, is derived from an Indian Sanskrit word, ‘dhyāna’, meaning ‘meditation.’ These three terms, dhyana, chan and zen, illustrate the migration of a particular form of Buddhist meditation practice and associated ideas from northern India to China and then to Japan. It also highlights how important the practice of meditation is to Zen Buddhism.

LEGEND has it that Buddhism was brought to China by Bodhidharma in the 5th CE – though there is evidence of migration along the ‘silk road’ in 2nd CE. Note his name – Bodhidharma. Bodhi = ‘awakening’ (from ‘budh’ to awake); Dharma – has many meanings including ‘the way things are’ (impermanence & interdependence) & a body of knowledge/teaching.

When Bodhidharma & others arrived in China they would have encountered two dominant modes of thought & being: Confucianism (concerned particularly with human order, regulation, hierarchy) & Daoism/Taoism (more concerned with natural order, spontaneity, non-hierarchical). A Daoist aims to live in harmony with, or in accordance with the Dao – the natural way of things – flow, process, change. Note similarity to Dharma (the way things are, process, anicca, impermanence). Bodhidharma may well have found an affinity with Daoist ideas and practices.

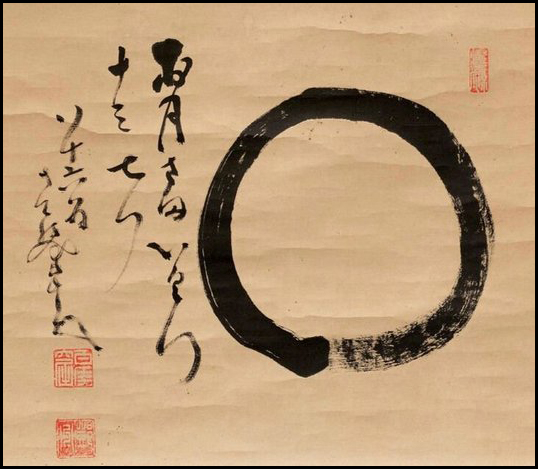

Bodhidharma (5th – 6th CE) (Daruma in Japanese) – known as the 1st Zen patriarch – associated with founding Shaolin temple & martial arts. Reputed to be very fearsome (see Hakuin portrait). His teaching summed up: ‘A special transmission outside scriptures and tradition.’ The practice of Zen involves seeinginto our true nature and realising awakening and fulfilment. Bodhidharma is said to have introduced ‘wall-gazing meditation’ into China. This form of meditation is a very distinctive feature of Zen practice in Japan, where it is known as ‘Zazen’ – which means ‘sitting meditation.’

There are three main traditions or schools of Zen in Japan: Soto, Rinzai and Obaku. I am focusing on the Soto tradition. I have no experience of Rinzai with its focus on koan practice, or Obaku and its chanting practices.

Eihei Dogen (1200-1253) – one of the most influential and highly respected of all Japanese Zen teachers. It was Dogen who, after a transformative trip to China, revitalised the Soto school in the thirteenth century. Dogen emphasised the practice of zazen – sitting meditation. He taught that everyone has the capacity for awakening and fulfilment – able to see into the nature of things and to live in harmony with impermanence and interdependence – by letting-go of habits of thinking, judging and clinging – a chance to experience unity with all the other beings and forces that make up our universe.

In an essay titled, Fukan Zazengi (‘Guidance for Zazen’), Dogen advised his students to set aside all cravings and to be at peace. Don’t sit thinking of past or future, good or bad, who am I, or how can I be enlightened. To practice zazen is not to try to be someone else, or to be somewhere else, or to analyse the human situation, or to achieve some goal beyond being present. Dogen advises us ‘neither to think nor not to think.’ How? By not clinging to thoughts, feelings, sensations or aspirations. Just being present, paying attention to what is happening from moment to moment – not dwelling on things or running around after thoughts and sensations. In zazen we let go of the ‘galloping around’ or ‘washing machine’ mind, and open to what we might call ‘mind-at-ease,’ ‘don’t know mind’ or ‘here and now mind.’ Zen in itself is being at peace, awakening, enlightening – and it is to be practiced whatever one is doing – at the heart of daily life.

*

Zen values simplicity, directness, action. Showing and pointing rather than telling and explaining. Zen practice IS to be awake – kensho, satori – and is open to everyone. Being mindful, practicing Zen, is central to daily life – hence the importance of cooks, gardeners and cleaners as exemplifying the way of Zen. Doing something mindfully, being present and awake, demonstrates your understanding. And the mind of awakening becomes everyday mind, ordinary mind – being awake to the miracle of being alive!!

The practice of zazen enables one to see more clearly what is going on and hopefully to act more wisely and effectively – to live in harmony with the ever-changing, interdependent nature of existence. It also enables one to appreciate oneself, other beings and the universe for what they are, and to see and value the beauty of everyday life.

But keep in mind that Zen practice – the practice of meditation, being mindful – needs to be framed and rooted in mindful ethics if it is to be a force for peace, wellbeing and sukha.

BE QUIET & STILL

PAY ATTENTION

LET GO

BE KIND

POETRY IS VERY IMPORTANT IN THE HISTORY OF ZEN (and Daoism) and something of the spirit of Zen and ‘awakening’ can be encountered in poems. Here are a few examples:

From the Zenrin Kushu (17th CE):

Sitting quietly, doing nothing,

spring comes and the grass grows

all by itself

BASHO (1644-1694)

Furuike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto

Dom Sylvester Houedard’s translation of this famous haiku goes:

FROG

POND

PLOP

LI PO (701-762)

Zazen on Ching-t’ing Mountain

Birds have vanished from the sky.

The last cloud drains away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.

Kobayashi ISSA (1763-1827) ‘cup of tea’

simply trust

do not the petals flutter down,

just like that

Teitoku Matsunaga (1570-1653)

the morning-glory that blooms

for just an hour

differs not at heart

from the giant pine

that lives for a thousand years

Reworking Basho (1644-1694)

the chestnut tree

next to my house

is on fire

with blossoms

but most men walk by

without noticing

Ryokan (1758-1831) (my version)

everything we build

will eventually

fall down

so, build well

and let

go

and three of my own:

we search far & wide

for wisdom and peace,

for a heaven that is always

out of reach,

yet when we let go of

our searching,

we find heaven and peace

are right here, right where

we are

*

drinking tea, cleaning teeth,

going to sleep, waking up

– everyday mind,

everyday miracles

– what more do we need?

*

we wash our plates

knowing there is no end

always another plate

to be cleaned